Likely health needs of people in contact with probation

We conducted a systematic review of the literature, which showed that overall, the health needs of people in contact with probation services (the National Probation Service or Community Rehabilitation Companies) in England is a relatively under-researched area. More research is needed to help us to build an evidence-base to enable research informed decisions to be made on how to commission and provide healthcare that meets the needs of this group. This should include consideration of how needs may vary across different groups, for example, women in contact with probation may be more likely to need access to some types of services than men.

The little research that has been conducted about the health needs of people in contact with probation in England shows that although they live in the community, they are likely to have different health needs from the general population.

This is something that needs to be considered by healthcare service commissioners as part of their role in reducing health inequalities and ensuring that services are commissioned that meet the needs of the whole population.

Findings from our systematic review about the health needs of people in contact with probation are summarised below. Where possible, we have also included up-to-date government statistics.

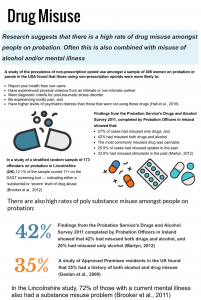

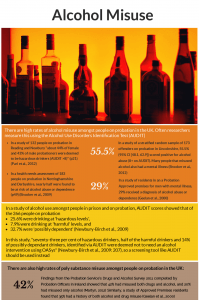

Substance Misuse

* Research points to a high rate of drug misuse and alcohol misuse amongst people in contact with probation

* Uptake of substance misuse treatment on release from prison has been shown to be low (Public Health England 2018). In 2017, just 6.6% of women and 3.9% of men on community orders received a drug treatment requirement, and 3.7% of women and 2.7% of men on community orders received an alcohol treatment requirement (Ministry of Justice 2018)

* Research by Mair and May (1997) with 1213 people on probation in the UK found that when asked about drug use in the last 12 months, reported rates were as follows: cannabis 42%, amphetamines 24%, temazepam 15%, LSD 14%, ecstasy 12%, magic mushrooms 10%, heroin 8%, cocaine 8%, methadone 8%, crack 8%, none of these drugs taken 42%, and 10% did not answer this question

* Often, people misuse both drugs and alcohol

* Substance misuse can also be combined with mental illness (dual diagnosis). In fact this is the case for many people in contact with probation

* Currently, such dual diagnosis can mean that people struggle to access healthcare as they are bounced between mental health and substance misuse services

* Local Authorities need to commission services that are able to work with people with this type of complex need

Link: Drug misuse info-graphic: https://my.visme.co/projects/n06q6pdn-ke7lp9q1zmeg29mw

Link: Alcohol misuse info-graphic: https://my.visme.co/projects/1jox07g3-ke7lp9q1zm6429mw

Mental Health

Very little research has been conducted into mental illness amongst people in contact with probation in the UK overall.

Of the research that does exist, some of it focuses on rates of mental illness amongst people housed in probation Approved Premises in the UK, including specialist Approved Premises for men with mental health disorders (Geelan, Griffin et al. 1998, Geelan, Griffin et al. 2000), and Approved Premises that work in partnership with psychiatric services (Nadkarni, Chipchase et al. 2000). In their study of 533 residents of seven probation Approved Premises in Greater Manchester, Hatfield et al., (2004) report the following rates of ‘known’ psychiatric diagnoses: depression, 14%; anxiety disorder, 6.9%; schizophrenia, 3%; personality disorder, 3%; affective psychosis/bipolar disorder, 0.4%; other psychoses, 2.1%; and dementia, 0.4%. However, people living in probation Approved Premises are not representative of the wider population of people in contact with probation.

Pritchard et al, report findings from two similar studies of broader probation populations aged 18-35 years. Here findings were based on questionnaires completed by staff. In the first study, they report that 25% of the sample of 261 people had a mental health disorder. In the second study 21% were reported as having a mental illness (Pritchard, Cox et al. 1990, Pritchard, Cotton et al. 1991). In a study of 183 people in contact with probation in two English counties, Brooker et al., (2009) report that 17% of participants listed ‘mental health’ as their greatest health problem (Brooker, Syson-Nibbs et al. 2009).

The only formally funded study of a stratified random sample of offenders in contact with probation in the UK found that 39% of people in contact with probation in one county had a current mental illness. The rate of psychotic illness was over ten times the average for the general population in the UK. This study also pointed to a high ‘likely prevalence rate’ of personality disorder, with 47% of the sample screening positive for this. In addition, this study showed that 72% of those with a mental illness also had a substance misuse problem (dual diagnosis) and 27% were experiencing more than one form of mental illness (co-morbidity) (Brooker, Sirdifield et al. 2011, Brooker, Sirdifield et al. 2012).

Research also suggests that some of those with personality disorder that are in contact with criminal justice services are at increased risk of having experienced childhood neglect, domestic violence, or physical, sexual or emotional maltreatment (Minoudis, Shaw et al. 2011). Consequently, they may benefit from access to psychological therapies.

Research points to difficulties in accessing care for those with a mental illness. For example, dual diagnosis and co-morbidity can form a barrier to service access (Melnick, Coen et al. 2008). There can

also be problems with continuity of care when people leave prison (Pomerantz 2003), particularly if information isn’t transferred from prison healthcare to probation services in a timely fashion, and if people encounter problems with registering with GPs prior to or upon release from prison.

Addressing mental health problems has been identified as a way of reducing reoffending and Mental Health Treatment Requirements are available as an option for people on community orders or suspended sentence orders with a mental illness that do not require immediate compulsory hospital treatment under then Mental Health Act (Khanom, Samele et al. 2009: 5). Guidance states that “CCGs and Local Health Boards are encouraged to engage with local criminal justice agencies to ensure that their commissioning activities and service design facilitate treatment access by offenders to enable the courts to consider an MHTR” (NOMS undated: 12). However, these requirements are currently under-used (Khanom, Samele et al. 2009).

Link: Mental health info-graphic: https://my.visme.co/projects/w4yzw1gr-owplnmnw0gd32zd6

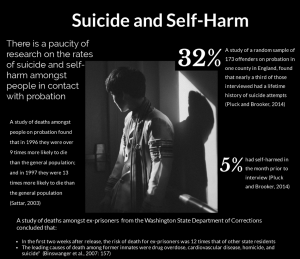

Suicide and Self-Harm

- A small body of research suggests that rates of suicide and self-harm are higher amongst people in contact with probation than amongst the general population in the UK and suicide rates are also higher in this population than amongst prisoners (Phillips, Padfield et al. 2018)

- Moreover, data suggest that the rate of suicides in the criminal justice system in the UK has been increasing (Phillips, Padfield et al. 2018), including amongst those in the community. Recent figures on deaths of offenders in the community in England and Wales show that “there were 285 self-inflicted deaths in 2017/18, an increase of 14% from 2016/17, and this accounted for 30% of all deaths” (Ministry of Justice 2018: 5)

- Individuals are particularly at risk during the first few weeks following release from prison (Binswanger, Stern et al. 2007, Phillips, Padfield et al. 2018)

- There are differences in suicide rates by gender(Corston 2007, Phillips, Padfield et al. 2018).For example, government statistics suggest that in 2017/18 from a total of 836 male deaths amongst offenders in the community 31% were self-inflicted. This compares to 25% of a total of 119 female deaths (Ministry of Justice 2018: 5)

Link: Suicide and self-harm info-graphic: https://my.visme.co/projects/mxnyg70d-g1d5koqen43326m7

General Health

- The results of our systematic review showed that there is very little research about the general health of people in contact with probation. Whilst the general health needs of people in prison could be used as a proxy measure (see for example the Health and Justice Annual Review 2017/18by Public Health England for some useful summaries), this an area where more research is needed

- Mair and May (1997) conducted a study with 1213 offenders on probation in the UK, and found that 49% stated that they “currently had or expected to have certain long-term health problems or disabilities listed on a show card (long-term was defined as for at least six months)” (Mair and May 1997: 17). When looking at health problems or disabilities lasting longer than six months, reported rates were often higher than in comparable data from the general population. 18% mentioned musculoskeletal problems, 15% mentioned respiratory system problems, and 14% mentioned mental disorders

- In a health needs assessment of people in contact with probation in two areas of England, Brooker et al., (2009) state that “SF36 scores revealed that offenders’ subjective mental and physical health and functioning was significantly poorer than that of both the general population and manual social classes using comparative standardized data derived from the Third Oxford Healthy Life Survey” (Brooker, Syson-Nibbs et al. 2009: 49). This study also found that 83% of the sample reported smoking tobacco, and 13% had been treated for a sexually transmitted infection

- Similarly, Pari et al., (2012) report that people in their study of 132 people in contact with probation in Reading and Newbury “had significantly lower SF-36 scores on all eight subscales than the general UK population” (Pari, Plugge et al. 2012: 21)

- Prison statistics indicate that a growing proportion of prisoners are aged 50+, suggesting that the probation population is also likely to include increasing numbers of older adults. The needs and costs of providing care for these individuals, some of whom may need specialist care arrangements as they pose a risk of harm to the public, needs to be considered by commissioners